|

|

Through Rose-Tinted Specs

Memories of Balbriggan in the fifties

copyright 2005 By Roger Turner

| Part 5: Food for Thought

| I don't half enjoy my Sunday dinner and always have for it is, by far, the best meal of the week. And when you are a little kid who has been half-starved since supper on Saturday, you start to crave food. Just the thought of walking through the door on our eventual return from Mass sent my stomach into raptures.

The gas had been lit before we left and the huge joint of beef left to slowly cook in its own juices. The process is coming to completion. Can't you just smell it?

---

| I suppose I was spoilt as a kid. In Sheffield, I used to spend most weekends at my grandparents house. Nan Calow was an old-fashioned cook, and cooked the most terrific meals on a great big range that dominated the main room of her house. The house had no gas and the only modern aid she had was a tiny two-ring Belling cooker for boiling sprouts (Ugh!), and an electric kettle beside her bed to quickly make a pot of morning tea. Everything else was cooked on the range, and I do mean everything: Roast Beef with Yorkshire Pudding and Roasted Vegetables all tasted fantastic cooked in that coal-fired oven. And it wasn't your cheap black-leaded range, but the top of the range model finished in ceramic cream. It didn't have temperature controls or thermostats; she regulated the heat by means of damper. The fire in the range was always lit, even in the summer, for it kept the water hot. Stevie Calow, my grandfather, was a chimneysweep and came home each day as black as the ace of spades and in need of a hot bath. It must have been a bugger trying to keep that house clean, but Nan Calow kept it spotless and never ever complained, until a few days before she died.

I have never known any woman work as hard as Nan Calow did. When Nan and Stevie first met she was in service in a big house in Sheffield and Stevie swept her off her feet. Hard work was a way of life back then and Nan never shirked from it.

I would sleep over most Friday nights and get up with Nan at six-thirty. She would bake up to a stone of bread every Saturday and did not rest until the last batch came steaming from the oven. Most of her bread was exchanged for goods or services from local traders, for Nan Calow made the best bread in the world. That was, apart from the world famous Balbriggan baker, Paddy Spicer.

Now I want you to honest. Hands up all those who got a clout for pulling the corners off Spicer's hot bread?

Yes, I thought so, and, although you can't see it, my hand was the first up.

Was it Oscar Wilde who said? "I can resist anything but temptation"

Well, to this little English lad and his Irish friends, the temptation to pinch the corners from hot bread was one temptation too many.

"Who's been nibbling the loaf?"

"It wasn't me."

"It was so!"

We had all raced out when the Spicer's van came so we all got blamed.

But what made Spicers bread so tempting and so, so, memorable was the fact that it smelt and tasted so good.

But then all food was good in the fifties, wasn't it?

Well, at least it was in Balbriggan. For a start, your local baker, without using any additives, baked bread freshly every day.

Yes! I know it didn't keep, it was never intended to keep, anyway, it never lasted long enough in the press to keep, we kids saw to that. Bread was made, bought and eaten on a daily basis. None of your mass-produced processed rubbish that passes for bread in the supermarkets nowadays. In fact, supermarkets had not arrived in the 50s. If you wanted bread, then you bought it from your local baker and made your own.

Balbriggan, like most other towns in the fifties, had several small grocery shops, and when you entered it was like nothing you can see today.

Firstly, your mammy sent you with a list and you handed it over to the shopkeeper who read it out in front of all those assembled for a gossip.

Half a stone of flour,

1lb of sugar,

Half a pound of sultanas,

10 plain biscuits.

Although big firms of millers were producing flour in 3lb bags, in some shops, flour and sugar still came loose in huge sacks that were much bigger than little me, and so heavy that it took 2 people to carry them. The shopkeeper ladled from these into paper bags and folded the top over in such a way that the contents did not escape. (Can you remember them blue sugar bags? Then you're older than you admit!)

Dried fruits came in wooden boxes or small barrels lined with thick greased paper and the fruits always came out stuck together in lumps.

Biscuits weren't in handy little cellophane packets, but came to the shop freshly baked and loose in big square tins. Each tin was put in purpose-built, hinged glass-topped display unit, and the biscuits counted out and sold by weight.

I can clearly remember climbing the steps into Derhams Grocery shop in The Square, Balbriggan, and having my senses being bombarded by a myriad of smells.

Let us take a look, or should I say sniff, at some of these smells on our shopping list:

Half a pound of cheese!

Cheese didn't come in them stupid little square packs that you are unable to open, but came in large round truckles, and were covered with waxed muslin that needed cutting with a sharp knife before you did anything else. A two-handle cheese wire was then offered to the cheese and a four-inch wheel sliced off the whole. This wheel was then cut through the centre and then into wedges ready for sale in the shop window. (It was a hanging offence back then to put cheese in a fridge, mind you, most people did't have a fridge in the fifties.) Not only did this process create powerful smells in the shop doorway, but also that cheese didn't half taste nice, for often it came direct from a farm not more than a few miles away that made the cheese.

Half a pound of butter

Even towards the end of the 60s, you could still find places that sold loose butter. Butter then came in 40lb blocks or tubs and once unwrapped, it was patted into half-pound pats then wrapped in greaseproof paper squares. To watch this process was one of the wonders of my childhood. The man wielding a pair of pats (or sometimes called paddles, was as much of a craftsman as a potter who moulded clay into pots. And this butter tasted much better than it does now and added to the aroma.

6 rashers of bacon

Bacon, in those days, was real bacon and had a hard dry rind covering at least a quarter inch of fat and then the pink meat. It came in long sides that were hung up in the shop to dry off. After a few days or so, the side was taken down and cut and boned before slicing. If the shop had a very good bacon trade then a tray of rashers was put on display in the window, if not, then it was cut to your own requirements

"Mammy says cut it on number 6 please."

The flitch of bacon was placed on to the bed of the bacon-slicer, held down with spiked clamps, and the assistant started off the large round wheel, slowly at first and gathering speed until the blade met the bacon. Whooosh! Whooosh! Whooosh! Whooosh! Whooosh! Whooosh! the slices of bacon fell onto the hand of the assistant, who soon had it wrapped in greaseproof paper and onto the brass scale. "One and nine pence there."

More smells filled the shop.

Now I can't remember if they had it Derhams, but one smell that we used to get in our local grocers was the smell of roasting coffee beans. My friend Barry Wood and his brother Frank used to do the roasting in the cellar of their dads shop and the aroma drifted up through the floorboards, and through the grate on the pavement, filling the air with the most wonderful aroma. Once roasted, the beans were left to cool and then ground to your requirements in the red Hobart coffee grinder. If you tried to grind the beans too fine the machine became blocked up.

With all these smells, no wonder I have fond memories of the period.

But all you youngsters shouldn't run away with the idea that there were no processed foods in the fifties. Far from it: Ideal and Carnation condensed and evaporated milk were staple foods whilst Ambrosia Rice pudding was a quick standby. For 1/6 you could buy a packet of Birds Pastry Mix and for 9d a packet of Symington's Table Cream, while 7d was enough for a pack of Royal Instant Pudding. Kraft had brought out Cheese Slices and 1/3 would buy you pack of them Dairylea Portions things. Mind you, there was probably more cheese on the grocers apron than in them little triangles.

And it wasn't just foods that your local grocery shop sold: For about 1/6 a tube of Harpic kept your toilet clean, while a 1/- worth of San Izal did the same for your sink and drains. Did you wash your clothes with Omo or were you a Tide person, or maybe you just scrubbed them with Sunlight soap?

Well, whatever you used, all these products and many more, added to the smell and atmosphere of your local grocer's shop.

If your order was too large to carry then the grocers messenger boy would deliver it on his rickety old bike! (done a bit of that in my time too) Ah, fond memories.

---

All this talk of food has made me realise that the roast will soon be ready back at my Aunty Eileens house, so lets hurry back there!

---

You must have realised by now that I have always enjoyed a healthy passion for food. And not just any food, but real home cooked food.

That Sunday when we finally sat down to eat we all enjoyed both the food and experience.

**********

| Now I hope you can forgive me for going off on a rant like this, but meat in the fifties was far tastier than most of the meat you can buy today. For a start, cattle were reared outdoors, fed on grass and not sent to market until the beast was well and truly ready.

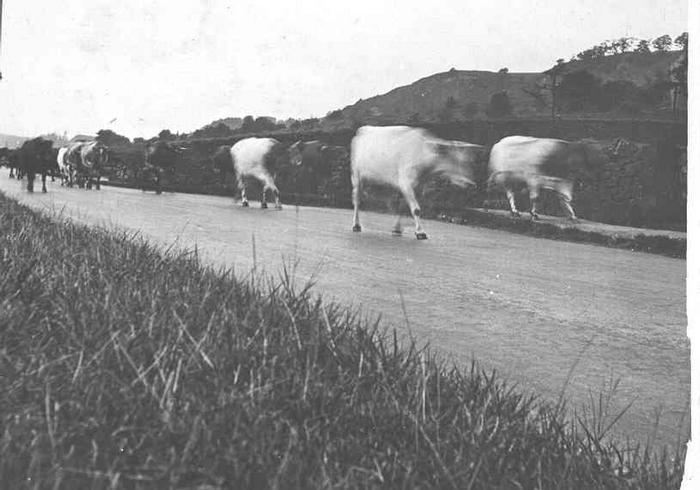

Now I don't need to tell you about cattle markets, for, like me, I bet you have many memories (both good and bad) of Balbriggan Cattle Market. But whatever else, Market Day for this little English lad in the fifties was memorable.

One dog and its farmer set off at first light with a line of walking cattle heading for the market. (I bet that doesn't happen now!) Soon, other farmers would join them, and from early in the morning the lanes and byways leading to Balbriggan would become jammed.

Yes, I know all about the shite they left rotting in the street, but that was part of the process.

"What are you doing with that old bucket?"

"Ah, sure, aren't I just going to shovel some up to put on me rhubarb."

"Well, you're welcome to it. I would rather have custard on mine!"

Do you knowwhat, I would give my right arm to be able to scoop up a few bucketsful for my garden nowadays. But in those days it was just left there to rot. Total waste!

I don't know about Ireland, but over here nowadays, most cattle never see a market. In fact, most cattle markets have now gone to the property developers.

Huge lorries now call at farms and the livestock are forced to climb in and endure a long journey in cramped conditions direct to a slaughterhouse hundreds of miles away.

But back in the fifties, many cattle and sheep came to market by foot, and from never more than a few miles away.

On Market Green, somewhere opposite the market house was a small old-fashioned butcherâ™s shop. I suppose the words Âold fashioned butchers shop™ are the wrong words to use, but a traditional butchers shop would better describe the establishment better.

Now as often happens, my memory chip has malfunctioned yet again, denying me access to the shops name. Despite this failing, the name Peter Clusky, has just appeared before my very eyes. Anyway, this butcher would buy his meat on the hoof at the Thursday cattle market, walk it across the road into his own pasture, and let the animal(s) rest. Monday, the beast was slaughtered, hung-up, dressed and left to cool. As a little lad I went to that shop most Mondays to watch, and I can still remember the steam coming off the liver and feeling how warm it was. The carcass was then left to hang for a few days and it was this drying-out and maturing process that gave tenderness and flavour to the meat.

When the meat was ready (and not before), the carcass would be cut into primal cuts with the best cuts left to mature for up to another week.

(Nowadays, within hours of slaughter the carcase would have been butchered, packed and sent for sale in a supermarket hundreds of miles away.)

The other difference to the meat of today is the fact meat then was covered in a generous and natural layer of fat that gave it texture and helped it to cook. But nowadays we have all been brainwashed into wanting only the very leanest of meat! That is, apart from me. I still buy fresh meat from a butcher in the market in Sheffield and I know just what will be tender and tasty.

The other butchers shop I remember is that of Tom Hagan. This was a very busy shop that sold meat produced on Jim Hagan's farm up at Clonard. (I'll be talking more about Jim's farm in a later episode of my epic saga.)

Tom Hagan not only sold meat, but also made his own Sausages, Black Pudding and my most favourite of foods, Real Irish White Pudding. No trip to Balbriggan was complete without buying a couple of pounds of Hagan's White Pudding to smuggle back home to Sheffield.

"Have you anything to declare?" The customs man in Liverpool would ask mother, thrusting a printed list under her nose for her to read.

She could honestly say, "No", for the same little lad who had smuggled several packets of tea into the country, and was now chatting away to the customs man showing him his new mouth organ, had it neatly hidden in his little case. Bloody good job they didn't have sniffer-dogs back in the fifties!

---

| Now, while I've been having a rant about the demise of quality meat, the roast potatoes have been cooking round the meat and it's time for the Yorkshire pudding to come out. Not these titchy little things you buy frozen in the supermarket, but a real large oblong Yorkshire pudding that rises at the edge of the tin until it becomes crisp. Nan Calow put sage, thyme and onion in her Yorkshire pudding mix, and, at her house in Sheffield, Yorkshire pudding was served with gravy as a starter before you had you main dinner. When money was tight, Yorkshire pudding and gravy was all some poor Sheffield families had for their Sunday dinner.

So, we are all seated round the table, grace had been said, and time for yours truly to tuck-in. My Grandad Turner always said I could make sparks fly from a knife and fork, and he was right.

"Don't gobble your food, Roger!"

I took little or no notice for I knew full well that when I finished first I would get first chance of second helpings. Meat was always my favourite, followed by Yorkshire pudding, Roast Potatoes with Green Veg following at the rear of the list. Like all children at that time we were expected to leave a clear plate, or else. Fortunately, sprouts were out of season in the summer months so I always managed to eat all before me.

Nan Calow used to tell me to eat my veg first (including sprouts) and then the meat would help get rid of the bitter taste. Nowadays I love sprouts, and, like a good little boy, I still eat all my veg first.

Second helpings and then... well, it could be fruit pie and custard, or, tinned peaches and cream, or, if we were very luck, my favourite, trifle.

Again, you'll excuse a tiny little rant, but real trifle, made with real whipped cream, should be one of the Seven Wonders of the World. And do you know what, I can't make trifle like we had in Balbriggan, because the cream we get now is too thin and watery.

Do you remember me complaining about a lack of decent soda bread in England? Well, I put it down to the milk we get nowadays.

Back in the fifties, cows were fed on grass and it was that grass that made milk creamy. And it was creamy too. Cows were all called names back then and usually milked by hand. Milk came to us in glass bottles with a two or three inch thick collar of golden cream. This cream was skimmed off the milk and, with a little sugar, whipped by hand for several minutes until thick and fluffy. Spread on top of the set jelly and custard, this confection was then topped off with glacé cherries. Wonderful. Nothing like those trifles you buy ready-made with that sympathetic rubbish that passes for cream now. Nowadays milk is produced from cows that are often fed with antibiotics and other treatments to make them produce even greater quantities of milk over longer periods. I now don't drink much cows milk, but pay more than twice as much per pint for lovely, tasty goats milk. Back in the fifties, goats were a common sight in Balbriggan and farms surrounding it. Even Paddy McGinty had one, (where's me mouth organ?) but his was a Bill. I bet you never see one being taken a walk nowadays. There was often one near the canal, but I can't remember exactly where, and I can never remember drinking goats milk, but I bet I did.

Rant over, and dinner over, so now it's time to clear away the plates and out comes the bottle Quix to wash the Delf.

After a good rest and cup of tea, it's time to really enjoy Sunday. I started this chapter off by bemoaning how boring Sundays were in Sheffield, and how much I enjoyed them in Balbriggan, well at home we just sat about, listened to some boring play on the radio, read books, and talked. But here in Balbriggan, we are off to spend the afternoon with our bathing clothes, buckets and spades and a football, ready to spend the rest of the day playing on the Front Strand...

To be continued...

|

|

|

|

|